An entry by Henry Jones for the Translating Cultures Exhibition

Mosaic is a text visualisation tool currently being developed as part of the Genealogies of Knowledge project (www.genealogiesofknowledge.net/about). Built as a plugin within a suite of free online corpus analysis software, it constitutes a novel attempt to develop the computer-aided visual encoding of concordances beyond the keyword-in-context (KWIC) indexing technique first developed in the 1950s (Luz & Sheehan 2014). While KWIC relies mainly on relative position to show connections between the keyword and its ordered left and right contexts (see Figure 1), Mosaic presents a multisemiotic graphical display (see Figure 2). It ‘translates’ patterns found in a concordance by means of the size and position of a patchwork of coloured word-tiles.

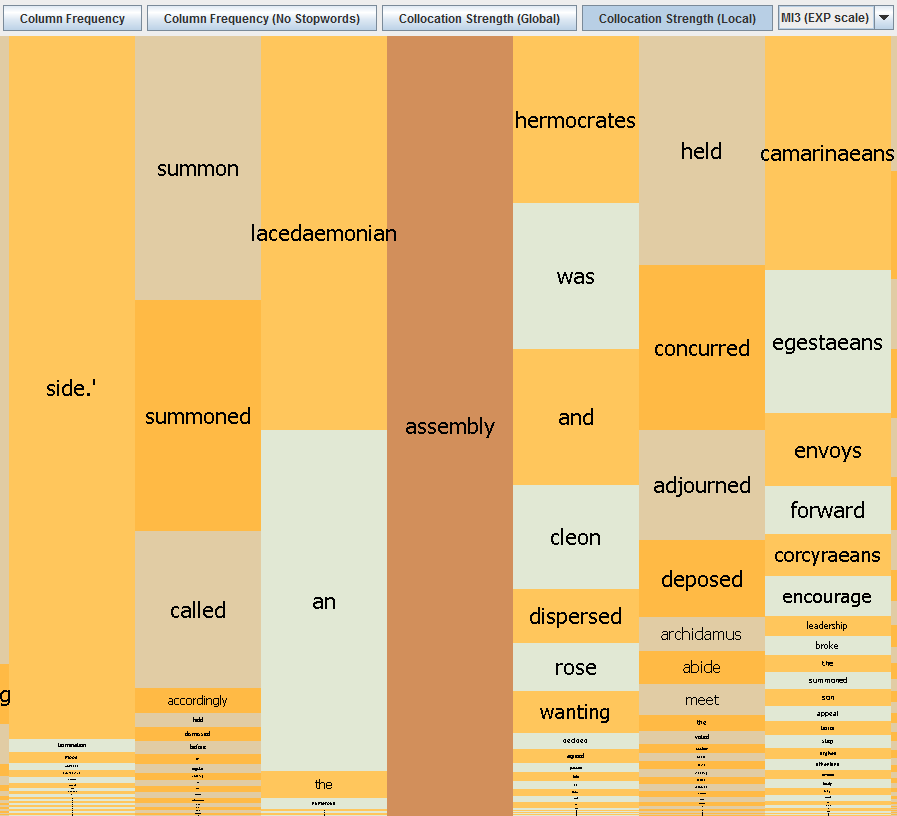

The plugin generates four different visualisations, each of which delivers a different perspective on the patterning of the chosen keyword in the corpus selected for analysis, but for concision we will focus here on the Collocation Strength (Local) view only. As can be seen in Figure 2, the keyword (in this case assembly) is highlighted both through its darker (brown) colour and its placement in the central column; lexical items that occur in each position to the left and right of this term in the corpus are then each allocated a differently shaded rectangle in the columns immediately adjacent to this keyword. The bigger the word-tile, the more significant the collocational relationship, as computed by the algorithm. In this particular Mosaic, that visualises patterns contained within Benjamin Jowett’s (1881) translation of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, the verbs summon and summoned are picked out as especially significant collocates of assembly, two word-positions to the left of this search term.

Collocational significance, or ‘strength’, is calculated using one of a selection of common statistical measures: when configuring the tool, the user may choose between scaling the tiles according to their MI score, MI3 score, Log-Log score or Z score. All of these statistics compare the positional frequency of a collocate relative to the keyword with this collocate’s absolute frequency in the selected corpus or subcorpus (Luz & Sheehan 2014). This visually enhances words that occur more frequently with the keyword at a specific position than would be expected based on the word’s frequency in the (sub)corpus as a whole. Thus, when studying Jowett’s (1881) translation and the ways in which he re-frames the agency of ordinary citizens in classical Athenian politics in particular, the Mosaic suggests we might productively begin our analysis by examining the extent to which this translator shows especial preference for the verbs summon, summoned and called in connection with the keyword. This pattern could be read as implying the existence of a higher political authority above and beyond popular democratic structures, unlike less marked choices such as held (which is shown by the software to be a less significant collocate).

In this way, the Mosaic plugin can often serve as a useful starting-point from which more detailed investigation of translation phenomena might develop. By translating features of a concordance into an alternative visual language combining modes of text, shape, colour and position, the tool helpfully illuminates possible avenues of research otherwise invisible to the naked eye, leading to new understandings of the texts under study. Nevertheless, by abstracting words on the page from their original material context and re-embedding them in a wholly different environment and configuration, Mosaic inevitably obscures just as much as it shows. Although cloaked in mathematical pseudo-objectivity, the nature of its algorithmic mediation is far from transparent, and its programming will inevitably foreground certain features of a concordance over others. In this sense, visualisation and translation pose the same challenge: the translation is not the original, the representation is not the reality. Consequently, such computer-generated visualisations can certainly aid some aspects of scholarship, but they can never fully supplant close reading, qualitative insight and human-led interpretation.

Figure 1: The KWIC concordance generated for the keyword ‘assembly’ in Jowett’s translation (1881) of Thucydides

Figure 1: The KWIC concordance generated for the keyword ‘assembly’ in Jowett’s translation (1881) of Thucydides

Figure 2: The Mosaic visualisation generated for the keyword ‘assembly’ in Jowett’s translation (1881) of Thucydides

Reference

Luz, Saturnino & Shane Sheehan (2014) ‘A graph based abstraction of textual concordances and two renderings for their interactive visualisation’ in Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces, AVI ’14, New York: ACM, 293-296.