Ilka Eickhof | Madamasr.com | April 20, 2017

Economic language has seeped deep into the everyday in western Europe, and is being imported into Egypt through funding.

Since local state and non-state funding is either scarce or limited in scope, a significant part of Cairo’s contemporary culture field — specifically visual art, dance and partly also theater — depends on funding from western European cultural institutions.

These institutions operate on the basis of programs and funding lines initiated by their respective government’s foreign cultural policy and cultural diplomacy, as well as revenues made mainly through language courses. The maneuvering of each institution’s cultural outreach is defined by the diplomatic ties between Egypt and each European state, which, depending on the political circumstances, allow more or less room for projects that question Egyptian politics and state power.

What are ‘creative economies’ and how do cultural institutions foster them?

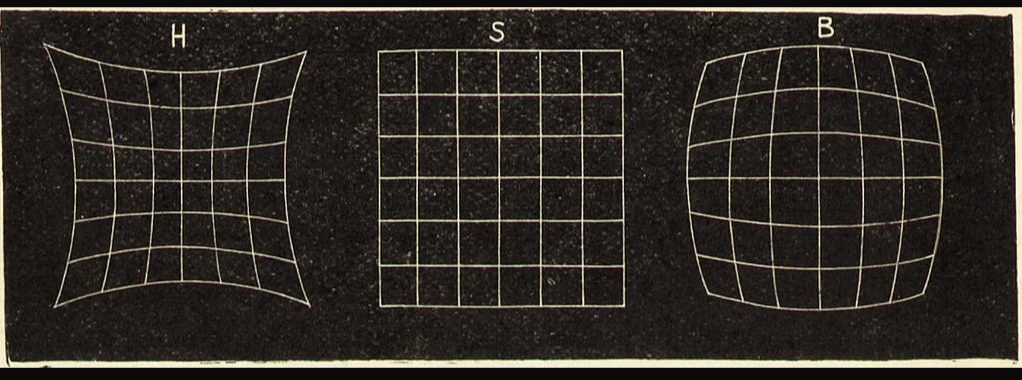

Most of these western European institutions are proponents of the so-called creative industries. “Cultural industries” and “creative industries” are not interchangeable terms, and the recent descriptive turn to the latter marks an economic shift from the traditional, material, industrial sector to an information and technology based communication and creativity sector.

“Cultural industries” refers to analytical discussions on the political economy of culture, and ethical and normative questions attached to it, first held among student radicals and others in the 1960s and 1970s counterculture, mainly in the UK. The term pointed to a critical approach to cultural production based on the works of sociologists like Bernard Miège and Nicholas Garnham.

“Creative industries,” however, hints at the economization of culture, also mirrored in the economic lingo increasingly used in the field. The arts and reasons for financially supporting them are described by English-speaking cultural policy makers globally through labor terminology such as industry, economy, strengthening capacities, sustainable and integrative growth, efficiency and productivity, audience development, social leadership, cultural entrepreneurship, reports and sales figures, cultural tourism, the creative class, and drivers of urban regeneration.

“Creative economies” are a global phenomenon that have become visible in Cairo in recent years through financial support for cultural projects and “entrepreneurships” in visual art, craft, literature, film, festivals, design and new media. Examples include the Goethe Institut extending its with the GIZ/Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit in 2012 to support “structures for cultural policy and the cultural and creative economy;” the “Development of Clusters in Cultural and Creative Industries in the Southern Mediterranean” project, led by the EU since 2014, and the Creative Industry Summit in Cairo, “a series of events and activities that capitalize on the huge potential of Egypt’s creative ecosystem and connects its stakeholders” taking place yearly since 2014. Also included is the British Council in Egypt’s “creative economy program,” launched in February 2016 to work with “the Egyptian government, industry organizations and businesses to support entrepreneurship, increase employment and grow demand for Egyptian creative products.”

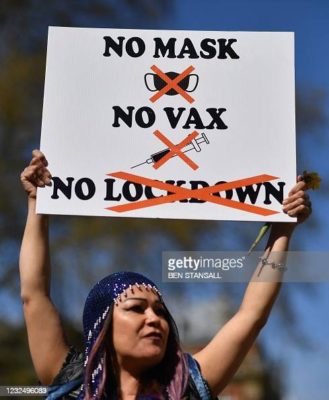

The shift from “cultural industries” to “creative economies” and a general ignorance of their history as reflected in their ongoing interchangeable use, hints at the degree of our accommodation to neoliberalism. In its broadest sense, neoliberalism describes a government policy that emphasizes human well-being realized through individual entrepreneurial freedom attached to so-called free markets, free trade and strong private property rights. The word “free” primarily insinuates a market detached from a state, and therefore also from any other form of structural inequality — hence the neoliberal American-dream slogan “Anyone can make it if they work hard enough,” currently often uttered by the northern hemisphere’s right-wing parties to dismiss structural inequities based on gender, race, cultural background, class, age or ability. But the state plays a permanent and necessary role in neoliberalization: The free market, like the western European cultural institutions through which creative economies are fostered in Cairo and elsewhere, is regulated on the basis of agreements between governments.

Although a certain gray area does exist, “free” is not only rhetorically misleading, but feeds into the construct of “free” versus “authoritarian” states. The desire of countries such as the UK, Germany and the US – in which free market policies and tight security apparatuses co-exist – to be seen as free and hold onto the powerful trope of humane capitalism influences cultural politics in various ways. This includes maintaining cultural representations – which transform societal critique into market-based objects -and pushing for an aesthetic sameness through regulating what is represented. One example of such marketization is the “mapping” of the contemporary culture scene and “identifying core actors,” a frequent undertaking by European cultural institutions (last year’s call by Denmark’s Center for Culture and Development and Danish Egyptian Dialogue Institute for a research assignment on creative industries in Egypt, for example), which not only matches historical tools of control and regulation, but allows for swift operations in accordance with a neoliberal labor structure.

“Creative entrepreneurship works really well, they do their own promotion, and resources can be shared, and the message is that creativity has a future to it!” a European culture worker in Cairo said to me, applauding self-regulation and self-promotion in the field. But if opportunities are rare and local political pressure grows, refusal becomes economically difficult and little space is left to create alternatives.

Development and the problems of unequal gifting

The EU’s cultural and creative sector is described by EY, a multinational professional services firm based in the UK, as a growing new industry with a “dynamic, knowledge-based economy” that generated 535.9 billion euros in revenue in 2014. But the growing creative industry is not just about market logics: it is also about identity politics. “Cultural and creative industries (CCIs) are at the heart of the creative economy: knowledge-intensive, based on individual creativity and talent, they generate huge economic wealth and European identity, culture and values,” stated the website of the European Commission on Growth in July 2016. It remained unclear though what exactly was meant by the construct of a common European identity when lifestyle differences and conceptions of morality are influenced less by geographical borders than by class, gender, race, age, education, life experience, nationality, and socialization.

Identity politics also play a role in culture’s interplay with development politics and initiatives because they position one party as developer and another as the party to be developed, influencing self-perception on both sides. Lingo and funding lines that see art as attached to a developmental function, rather than as purpose-free and containing a creative function in itself, thus create asymmetric relationships and power dynamics. Examples of this tendency in western European foreign cultural funding include the UNESCO Chair in “Cultural Policy for the Arts in Development,” inaugurated in 2013; the strategic group for “culture in EU external relations and development policies” developed in 2016 by the European Commission and the High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy; the diplomacy platform “More Europe,” funded by the Goethe Institut and the British Council among others, which publishes advocacy papers on “Culture in EU development policies;” and the “Cultural Diplomacy Platform” established in 2016 and led by the Goethe Institut, with the British Council, the European Cultural Foundation, EUNIC Global and the Institut français as partners. “The creative industries also have a vital role to play in development, both in terms of employment and wealth creation, and as flagship businesses for their culture or nation,” said Ciarán Devane, chief executive officer of the British Council, in a 2016 interview.

A funding situation in which donors give to receivers under umbrella topics that frame funding lines alongside developmental politics attach aid to a clear function, which breaks down the notion of monetary support as a gift, aid or intention-free support. But the concept of the gift does not exclusively indicate something material — it entails symbolic functions too. In the ideal situation, giver and receiver are in relatively balanced positions, and each is able to reciprocate in order to sustain a cycle of gift and counter gift. One can speak of equivalent exchange only when both sides have rights and duties toward each other, and the exchanged goods are of similar value – whether material or immaterial. But gift-giving in the form of aid depends on a debt balance between giver and recipient that cannot be turned around.

Developmental aid can be seen as both gift and commodity, a contradiction which reveals the asymmetry of the donor-receiver relationship. Within Cairo’s small contemporary art scene, this dynamic is often negated or substituted by notions of friendship. Ambivalences arising from complex social relationships between funders and donors are echoed in vocalizations of personal disappointment when local artists act unexpectedly (that is, not according to the institutionalized way funding works, with budget overviews and responsibilities, proposals and reports) – critiquing funding when receiving or applying for it, for example, or not reciprocating friendliness after funding or employment is terminated.

Labor, creative economies and the everyday

The concept of failure is a good example of how economic language has long since seeped deeply into the everyday in western Europe, mostly in relation to time: seeing a friendship or romance as an investment, failure or waste of time, treating oneself well as reward or compensation for a job or tough time, time efficiency, feeling bad about purpose-free idleness, the concept of procrastination. Even the class-related idea of vacationing is paired with idleness, versus efficiency and work: vacations are permitted idleness, as escaping “real life” (read: work) is thought to re-energize the worker to return to their implicitly unpleasant, energy-draining work. This constructed division between labor and vacation is mirrored in our language and self-governance: feeling overworked, undeserving, guilty, failed, stressed out and tired.

Self-perception regulated through economic definitions of failure and success leads to exploitation of one’s self and of others, often without anyone being able to notice or object. Most cultural producers and knowledge workers, such as journalists, academics and artists, are exposed to flexible work times (often meaning 24/7 availability), volunteering, illegal employment, long-term temporary employment, subcontracting and freelancing, all of which enforce competition for funds and employment. Self-regulative labor can have compound negative effects physiologically and psychologically: sleep deprivation, unbalanced diets, eating disorders, stress, competitive pressure, loneliness, depression and performance anxiety have all exponentially increased among cultural producers and knowledge workers in recent years (see here and here). This precarity produces a general preoccupation with insecurity.

This condition is often normalized through both the construct of freedom and the casual exchange of health repercussions. Statements like “I’m so stressed and overworked,” “I worked all night,” “I published three peer-reviewed articles and organized two festivals in three weeks,” and “I am working on a similar project, but can’t tell you about it” do not lead us to object to these labor structures but to reinforce them due to the insecurity they generate on all levels – money (free labor or low budgets and wages), time (limited contract or project duration), health (lack of insurance, illegal employment, no pension, social security) and legal status (no work visa, free and contract-free labor). Apart from long-term repercussions like poverty in old age (specifically of women due to gender imbalance in the cultural sector and in terms of part-time jobs), neoliberal work structures thus enforce competition (as one is potentially threatened by others who are precarious as well) and prevent resistance (such as negotiating conditions or declining certain projects, funds or employment positions).

Limited freedom of choice is less visible because insecurity seems ineluctable. The use of force is not executed on the premise of repression and assault (as in bodily harm) by others, but executed ourselves as “entrepreneurs of the self” on the basis of precarity and dependency. The invisibility of this kind of regulating power disguises structural conditions like racism, classism and sexism as personal responsibilities, and therefore personal matters of success and failure. “Take it or leave it, no one forces you to take our funding,” was the response of one employee of a European institution to criticism of western European funding in Cairo in 2014; a comment which not only refuses to historically locate European funding of contemporary art and culture in Cairo, but also declines the dependency and symbolic violence of the structural system behind it. “If you can’t find an opportunity, create one,” said an Egyptian cultural practitioner during a public discussion on arts and funding in Cairo in 2016. Both statements, although spoken by both “giver” and “receiver,” reflect a neoliberalization of the arts that leaves little choice due to a lack of alternatives and a surplus of economic pressure.

Social inequality and creative economies

This kind of labor structure benefits a specific social class and therefore perpetuates social inequality: Some people can better place themselves in the creative industry than others, often due to class-related means of knowledge and education — language skills, habitus, passport, jobs and networks. The pressure of neoliberal labor turns networking into an investment that makes even unpaid or barely paid positions like volunteering, interning or being hired as a research fellow for extended periods of time, seem worth it. Bodily presence becomes an investment in itself — a fact especially noticeable to those who must coordinate multiple jobs to make a living and cannot invest in being present without compensation, therefore missing out on opportunities which might enable them to be present the next time. A recent example is an informative event for the public, organized as part of the music festival Masafat, titled “International Opportunities and Networks for Artists,” which invited local cultural practitioners to engage in conversation with “representatives from cultural institutions in Cairo such as the British Council, the Goethe Institut and others” on “how to engage with these institutions and apply for different types of support.” The event took place on the afternoon of a work day, and attendees exchanges email addresses with the institute’s representatives at the end. Those unable to attend missed out on information about collaboration and support, but also on a “networking opportunity.”

Western European foreign cultural politics and politics of labor thus intersect and influence social groups in relation to their financial, social and symbolic means, reproducing a complex structural social inequality in the conditions of cultural production. It is important to point out that this article focuses on the social dynamics and ambivalences that accompany European funding in the Global South in general, rather than projects themselves, their outcomes, and their possible meaningfulness for participants and organizers. But the reinforcement of a structure in which many cultural practitioners compete for few opportunities favors producing over creating – a dynamic one artist has described to me as “cookie-cutter.” Cultural projects which favor certain aesthetics as well as accepted, uncontroversial content, reproduce an unquestioned consensus and sameness. “There’s not a community but an economy around us that we find ourselves a part of,” an artist told me in 2013. “And it seems to be the only economy we’re able to be part of, and this is one of the major crises of the nonprofit culture scene of this region. That we are not able to find an alternative to the economic model we are living within.”

The situation painted here in black and white is complex and many-layered; the labor structure on the basis of which creative economies operate allows for diverse levels of engagement, exposure and security. But the symbolic capital for those working in precarious culture and development positions varies immensely depending on passport and nationality. “Anyone involved in [the Arab art world] who is white who ‘dares to take it on’ is seen as a badass and risk-taker, so people find it very alluring,” a local artist told me. While white North American or western European practitioners here have the ability — whether they use it or not — to milk their experience in future employment for decades, the creative industry doesn’t leave much choice for those operating on more precarious levels. Similar dynamics can be found in academic work and journalism. A related problem here is the presence of white Europeans in high positions in arts organizations in Cairo. Depending on the institution, this is problematic when it leads to “white programming” (texts, libraries, invitees, project ideas), which necessarily leaves blank spaces and untold narratives through the power of the western educational canon. It re-enforces the idea that a local person cannot possibly hold such a position, making western education seem more aspirational. “Even if you don’t care about the North, the installing system is the North,” wrote a local arts practitioner on Facebook in 2016.

Ultimately, chasing institutions with budgets and preparing proposal after proposal while trying to make a living from often poorly paid short-term contracts — a norm imported as part and parcel of neoliberal “creative economies” — does not allow for the idle moments in which relationships are grown, spaces sustained, and in which collaborations are not a “waste of money and time” but alternatives to a funding system that emphasizes the fast production of spectator-tailored events. These labor dynamics feed into the asymmetrical power relationship between receiver and donor, structures of dependence on multiple levels, and funding reaching specific types of people. All these factors reinforce international and local social inequalities, and leave little space or choice for creating and thinking about alternatives. But examining the governmental structures of insecurity which regulate how we conduct our lives and our subjectivities makes it possible to see the complex structures of economic exploitation, obedience, subjugation, and delusions of self-empowerment, in arts and culture and beyond.