Aileen Das | British Library blog

Link: https://www.bl.uk/greek-manuscripts/articles/the-transmission-of-greek-philosophy-and-medicine

[Philosophy] does not belong to the Greeks alone, but can be acquired by all who are diligent, whether they are Greeks or Barbarians.

Here, the Syrian bishop Severus Sebokht stresses the universal relevance of philosophy. Working in a monastery near the Euphrates River, Severus acknowledges the ancient Greeks’ expertise in the field, but remarks that Christians like himself can learn it too.

While Greek philosophy and medicine come from a pagan past, these sciences had cross-cultural appeal throughout pre-modern history. Christian authors such as Severus studied the logical works of Aristotle (384–322 BCE) to hone their debating skills against theological opponents; the writings of Galen (129–c. 217 CE) were essential resources for monks treating ailing brothers in isolated monasteries.

As this article will discuss, the transmission of Greek philosophy and medicine was an international phenomenon, which involved bilingual speakers from pagan, Christian, Muslim, and Jewish backgrounds. This movement of knowledge spanned not only religious and linguistic but also geographical boundaries, for it occurred in cities as far apart as Baghdad in the East and Toledo in the West.

Greek in Alexandria

Athens and Rome were famous centres of learning in antiquity, offering enterprising philosophers and physicians the opportunity to amass students and to gain wealth and prestige. However, under Roman rule, Alexandria rivalled Athens and Rome as the place to study philosophy and medicine in the Mediterranean.

Alexandria, and Egypt in general, played a prominent role in transmitting the works of Greek philosophical and medical thinkers. After Alexander the Great’s death in 323 BCE, the general Ptolemy and his successors made Alexandria the capital of their Egyptian Empire. They supported the building of the famous Library of Alexandria, where scholars copied and stored books that were borrowed, bought, and even stolen from other places in the Mediterranean. The librarians gathered texts circulating under the names of Plato (d. 348/347 BCE), Aristotle and Hippocrates (c. 460–c. 370 BCE), and published them as collections.

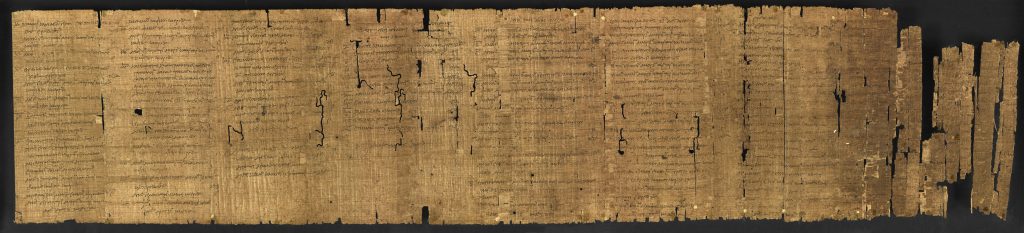

Egypt has a climate especially conducive to the growth of papyrus plants, so it was an important site for the production of texts throughout Graeco-Roman antiquity. Its desert has preserved some of our earliest surviving Greek philosophical and medical papyri. For instance, Papyrus 131, dating to c. 100 CE, contains a nearly complete copy of The Constitution of the Athenians, which is attributed to Aristotle. The work details the history of the Athenian government until 328–325 BCE, and it appears not to have been circulated with Aristotle’s other writings.

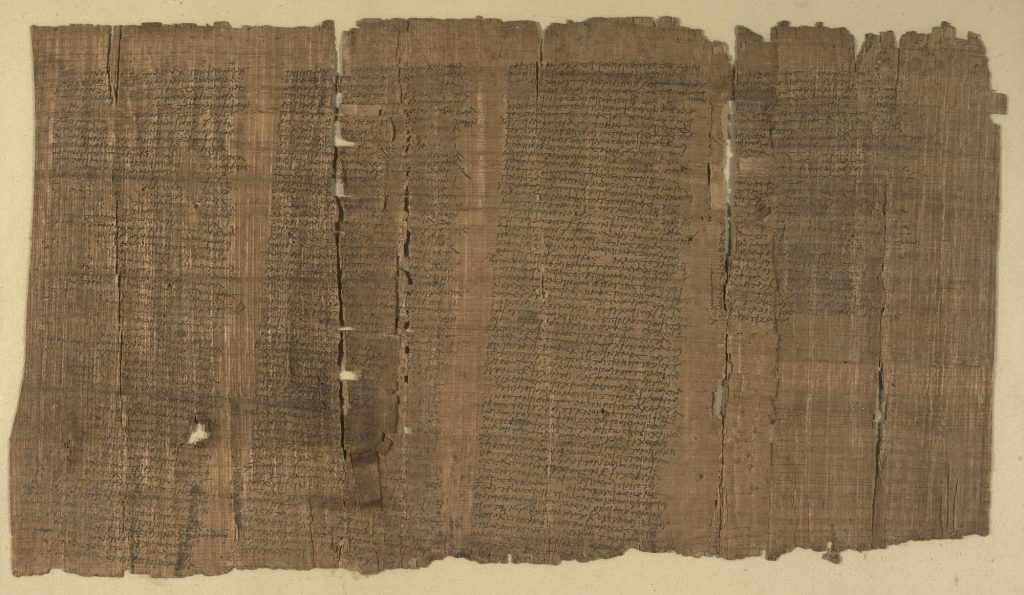

Another papyrus, containing the work of an author known as Anonymus Londiniensis, also comes from Egypt of the 1st century CE, and it surveys 5th- and 4th-century BCE writers’ views about the origin of disease.

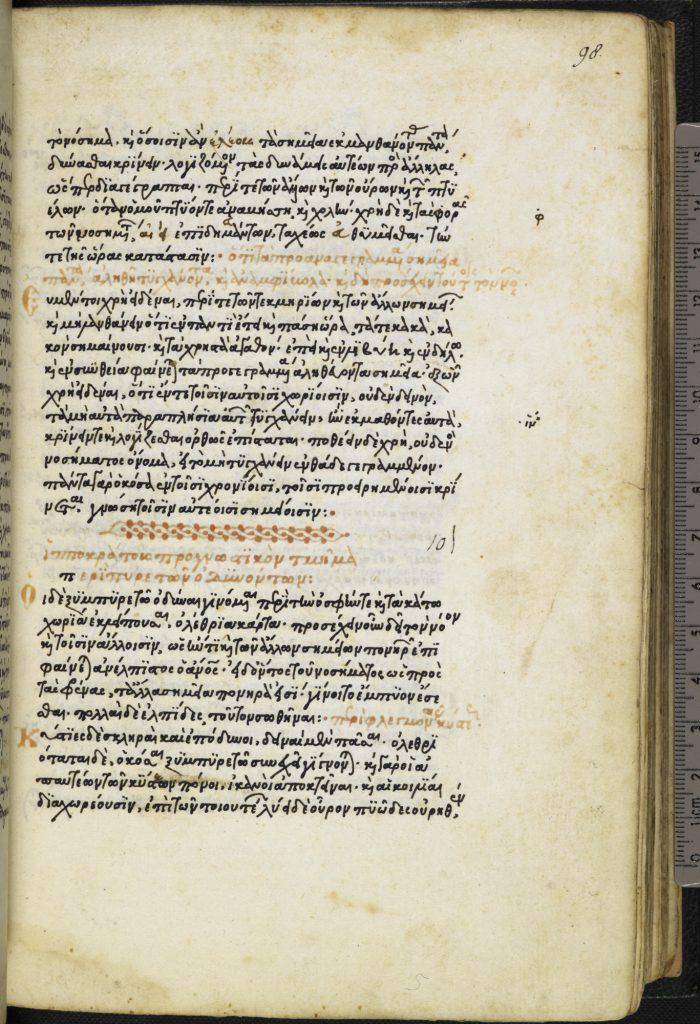

Meno, a pupil of Aristotle, seems to have composed part of the text, and he quotes Hippocrates as believing that ‘breaths’ (phusai) create disease in the body. The books of Galen, who hailed from Pergamum but grew popular in Rome, constituted the core of the medical curriculum in Alexandria, while philosophical study focused on Aristotle’s body of work rather than Plato’s.

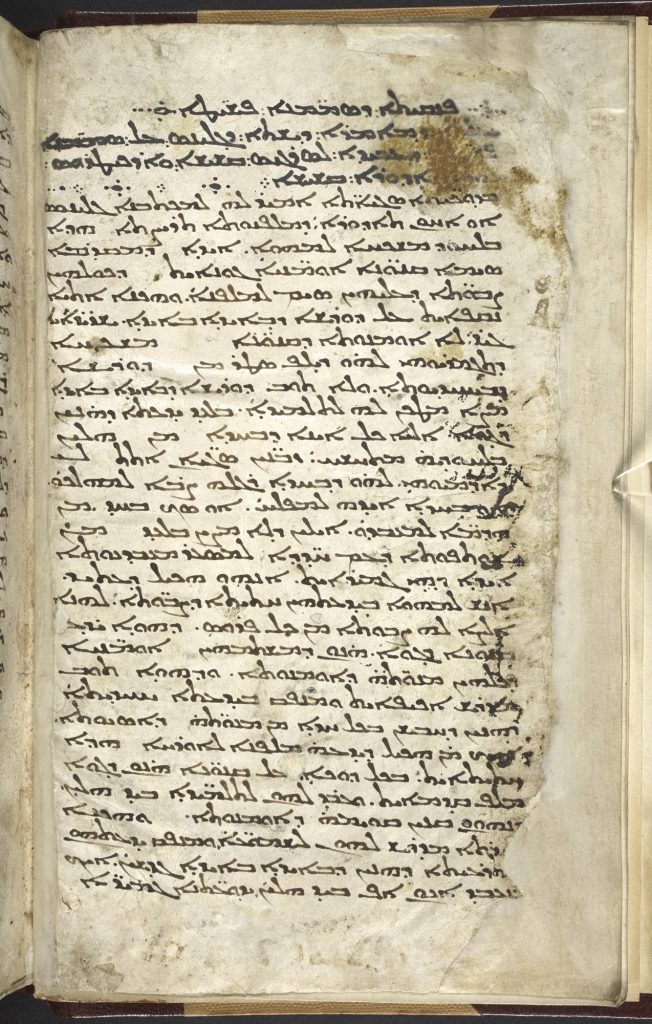

Young men of financial means travelled from distant communities to receive instruction in Alexandria. The priest Sergius of Reshaina (d. 536 CE) trained in medicine and philosophy there before returning to his home in northern Syria to become doctor-in-chief. Fluent in both Greek and his native Syriac, Sergius translated around 30 works of Galen and philosophical treatises such as the pseudonymous On the Universe, a cosmology ascribed to Aristotle. Most of Sergius’ translations are lost, but a copy of his Syriac version of Books 6–8 of Galen’s pharmacological treatise On the Powers and Mixtures of Simple Drugs survives.

The rise of Arabic

In 642 CE, following a 14-month siege, the general ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ (c. 585–664) captured Alexandria for the Rāshidun Caliphate (632–661), and thus ended eastern-Roman rule of Egypt. Medical and philosophical instruction seems to have continued in Alexandria for more than a century after the Muslim conquest.

Baghdad, however, became an intellectual epicentre under the ʿAbbāṣid regime in the 9th–10th centuries. There, caliphs such as al-Maʾmūn (r. 813–833) sponsored the translation of texts like Aristotle’s Topics into Arabic to learn the methods for constructing logical arguments against political and religious rivals (both Christian and Muslim).

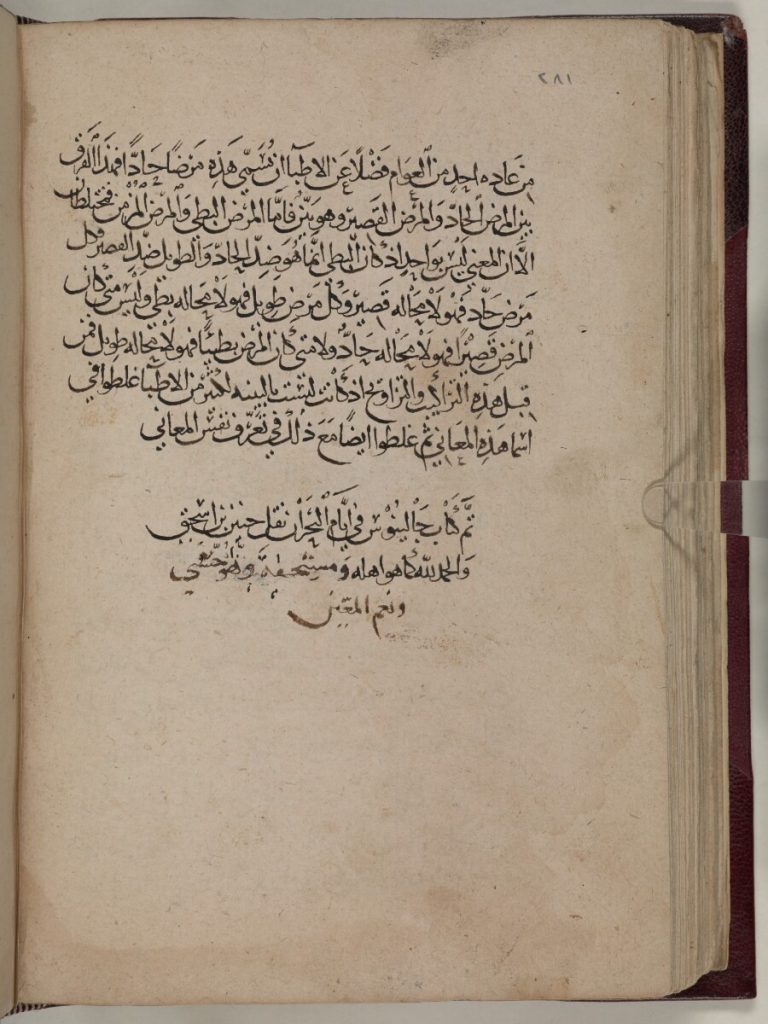

Governmental officials and scientists also paid large sums of money to pagan, Christian, and Muslim translators, who knew Greek, Syriac and Arabic, to render Greek philosophical and medical works into Arabic for private use. The most famous translator of the period was Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (d. 873/877), a Christian physician from south-central Iraq. His workshop, which included family members and other skilled translators, produced precise Arabic versions of Galenic, Aristotelian, and Neoplatonic writings. Ḥunayn often worked directly from Greek manuscripts that were acquired from the neighbouring Byzantine Empire. Sometimes lacking a Greek manuscript, Ḥunayn utilised earlier Syriac translations by Sergius of Reshaina to make his own Arabic versions.

End of the ʿAbbāsid Empire

The 10th century saw the disintegration of the ʿAbbāsid Empire, which had stretched at its peak from central Asia to northern Africa, into smaller caliphates. With this loss of power, ʿAbbāsid caliphs in Baghdad no longer had the resources to support costly translations of Greek texts.

However, Christian kings and clergymen in other parts of the Mediterranean, such as Sicily and Spain, financed the translation of Arabic versions of Aristotle, Galen, and other Greek authors into Latin.

During the 12th and 13th centuries, Toledo became renowned for this Arabic–Latin translation activity, partly because it housed several libraries with rich stores of manuscripts. Prior to the Christian conquest of Toledo (1085), the Caliphate of Córdoba had established Toledo as a provincial capital. Muslim and later Christian rulers largely protected the city’s Jewish, Christian, and Muslim communities, which had adopted Arabic as a lingua franca.

Gerard of Cremona (1114–1187) was the most prolific translator working in Toledo. Dissatisfied with the teachers in his native Italy, Gerard travelled to Toledo where he learned Arabic from Jews and Muslims, who appear to have assisted him in the translation of Arabic books into Latin.

Although the ʿAbbāsids claimed that the Byzantines had no interest in Greek philosophy and medicine, scribes copied and preserved texts of Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates, and Galen throughout the Christian Empire’s long history (c. 330–1453). The Jewish doctor Simeon Seth (11th century) even translated Arabic books into Greek.

The Ottoman conquest

The Ottoman conquest of the Byzantine Empire in 1453 caused many Greek scholars, who had manuscripts in their possession, to flee to the Christian West. Places like Florence, Rome, Venice, and Padua developed a reputation for Greek learning, for there, Byzantine émigrés offered instruction in their native language and established libraries from their manuscript collections.

As more Europeans learned Greek in the 15th and 16th centuries, printing ancient scientific literature became a lucrative business. Aldus Manutius (1451–1515) founded a publishing dynasty in Venice, which was responsible for the first printed editions of Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen.

A Cretan, Marcus Musurus (c. 1470–1517), assisted Aldus in the editorial work, and travelled to different libraries to consult manuscripts formerly owned by Byzantine emigrants. Our modern editions of Greek philosophical and medical works depend to a great extent on Aldus’ prints.

Aileen Das is Assistant Professor of Mediterranean Studies at the University of Michigan.